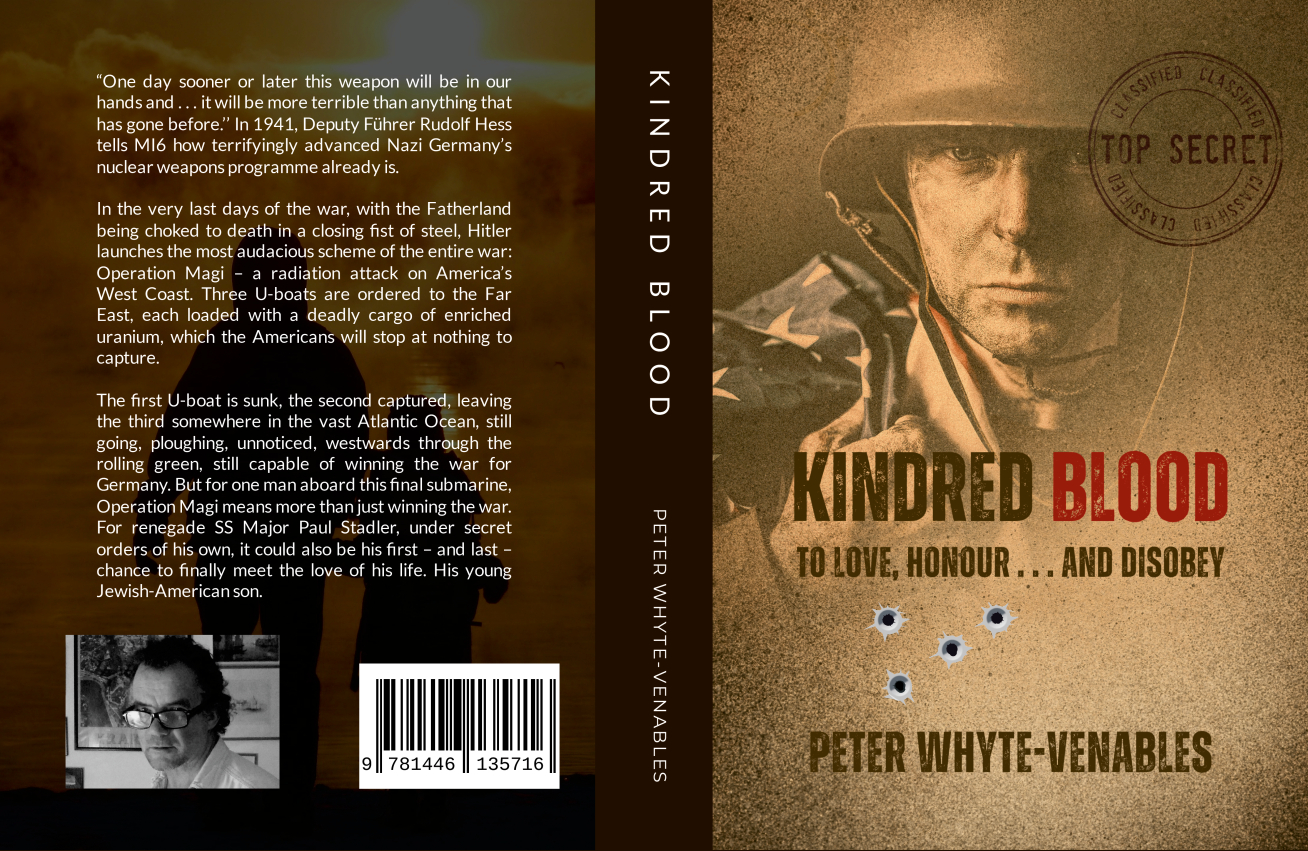

Kindred Blood

“One day sooner or later this weapon will be in our hands and . . . it will be more terrible than anything that has gone before” - 1941 Deputy Fuhrer Rudolf Hess tells MI6 how terrifyingly advanced Nazi Germany’s nuclear weapons programme already is.

In the very last days of the war, with the Fatherland being choked to death in a closing fist of steel, Hitler launches the most audacious scheme of the entire war: Operation Magi – a radiation attack on America’s West Coast. Three U-boats are ordered to the Far East, each loaded with a deadly cargo of enriched uranium, which the Americans will stop at nothing to capture.

The first U-boat is sunk, the second captured, leaving the third somewhere in the vast Atlantic Ocean, still going, ploughing, unnoticed, westwards through the rolling green, still capable of winning the war for Germany. But for one man aboard this final submarine, Operation Magi means more than just winning the war. For renegade SS Major Paul Stadler, under secret orders of his own, it could also be his first – and last – chance to finally meet the love of his life.

His young Jewish-American son.

Publication Date: Mar 10, 2024

Language: English

ISBN: 9781446135716

Category: Fiction

Copyright: All Rights Reserved – Standard Copyright License

Contributors: By (author): Peter Whyte-Venables

Pages: 497

Binding: Perfect Bound

Interior Colour: Black & White

Dimensions: A5 (5.83 x 8.27 in / 148 x 210 mm)

An excerpt from ‘Kindred Blood’:

As he looked down at the low, partially-forested mountains of southern Bavaria, the pilot knew that only one of two likely scenarios awaited him. One would make him an international hero with a guaranteed place in the annals of European history; and the other would have him broken and bleeding within a week.

Either case would depend upon who was waiting for him down there now at the rendezvous. If it was the scientist, there was a good chance that the pilot would see his wife and son by the end of the month; but if it was the Gestapo, the best he could hope for was that it was only him left broken and bleeding by the end of the week, and not his family also.

The lake would be the first landmark to look for, and when it did indeed appear he banked and at once saw the strip of green he was seeking, bright against the dark of the forest. Nearby, a bonfire in the yard of a woodsman’s cottage gave an indication of wind direction and strength. He made a straight flypast, along the length of the meadow, low and fast, but saw, as he had hoped, nothing, so he brought the Messerschmitt round in a wide circle, lowering the undercarriage and flaps, and prepared to land. With only a slight swing to port, which he gently corrected, he throttled back to 100kph and made the approach.

A sudden drop over the tree line and he was down, throttles right back, stick loose in his hand, brakes full on, and by zig-zagging as widely as he dared on the rough pasture, he was able to regain control by midway of the length of the field. Blipping the engines, he taxied over to the far corner, where, the slipstream flattening the turf behind him, he turned to face the field, left the throttles at tick-over, released his straps, lifted the canopy and stood up on his seat to look around at the peaceful scene.

Nothing. Nobody ran out to greet him from the shadows. Beyond the growl of the engines, there were no shouts, no shots. He clambered out onto the wing, and only then saw a dark figure striding rapidly towards him – or rather, towards the starboard engine, whose still-turning blades would have decapitated an ox. He took half a second to confirm who it was before yelling, “Look out!” and waved the pale face back to the wingtip.

Obediently, the man complied and came round to stand mutely below, while pilot Alfred Horn – it was typical of Rudolf Hess that he should have given himself a nom de guerre with Hitler’s initials – opened the rear canopy, lifted out the spare parachute and jumped to the ground.

“Hello Willi,” he shouted through the gale that whirled around them, and then he stopped, staring. “What are you doing?”

“What do you mean?”

“I said to wear warm clothes!”

“But I am wearing warm clothes.”

“For God’s sake, Willi, I didn’t mean here! It will be minus twenty-something at eight thousand metres. Look, stuff the hat and the case in here . . . that’s it. Wait.” He climbed back up and reached into the recess behind the rear gunner’s seat and retrieved a bulky grubby-white object. “Put this life-jacket on. It should keep you a bit warmer.” He picked up the gunner’s parachute again. “Right, now put your foot through here . . . and the other one. There, that all fits well enough.

He helped the man up and into the rear seat and strapped him in, showed him the levers for operating and releasing the canopy and how to turn on the oxygen, and finally returned to his own place in the cockpit.

Another little taster from ‘Kindred Blood.’

The moment Michael McInnes opened the front door of his cottage, he felt that something was wrong.

But in the balmy mountain air of a summer’s night the notion seemed absurd, so he stepped out, turned to close the door quietly – the more sleep that could be had within Glen Cottage the better – particularly for eleven-month old Rose.

He paused and looked around, his unease receding. This far north, the sky still held – even at ten o’clock – the residual glow of what had been a glorious sunset, and over to the south-east a nearly-full moon had already cleared the horizon, promising an excellent night for flying. The sky was windless, the valley silent, and McInnes felt a profound sense of peace as he breathed in deep the pine-scented air.

He walked across the yard to where his van was parked beside the old barn. Wartime restrictions permitted him only a small amount of petrol each month, and he reserved this mostly for these infrequent night-time trips to Dungavel House, whenever it was his responsibility to prepare the landing ground for unexpected guests.

During the hours of daylight he bicycled to work, but the wooden leg strapped to his right knee, a reminder of the fracas at Dunkirk that would stay with him for the rest of his life, made bicycling an awkward business at any time, let alone along nearly five miles of winding country lane in the dark, in a hurry.

As he took the ignition key from one pocket, he checked in another for the bunch of airfield keys, the ones for the hangar, the workshop and the fuel store, and for the newly-installed main gate where the drive met the Glasgow road.

He had just placed a hand on the door handle of the van when a voice spoke from somewhere to his right. “Micky?”

It was the voice of a woman, and he recognised it immediately. A figure stepped from the end of the barn, and even in this weak light he could make out the outline of a skirt, and the gleam of pale, shoulder-length hair.

“Helen!”

It was Miss Niven, the new help at the House, a warm, easy-going Englishwoman of about twenty-five, recently posted from Braemore Lodge over on the east coast, where she had been a housekeeper in the service of Lord Portland, friend of Dungavel’s Duke of Hamilton. McInnes was surprised to see her here now.

“Hello, Hel –” he said and blinked as a sledgehammer struck him on the breast bone. He staggered against the van and opened his mouth to speak but he was breathless with shock and no sound emerged. He knew that he should make a connection somewhere between the strike and the shock but his legs buckled and he felt the hard round shape of the van wing scrape up his back as he slid to the ground where his head hit the gravel and he stared up at the high thin clouds. He lay there, blinking at the pain, still trying to make sense of it and frowning at what Sarah would say when she found him out here and trying to picture little Rose’s face . . .

Michael McInnes watched the figure appear above him, silhouetted with its halo golden pretty against the darkening sky, and he heard the gentle crunch of shoes on stones beside his head and the hoot of the tawny owl that had made her nest in the woods across the stream, but he did not hear the soft click – really no more than the snap of a man’s fingers – that fired another bullet.